Cave tours are becoming increasingly popular, largely due to the mesmerizing presence and continuous growth of geological formations known as speleothems. Among the many types of speleothems, stalactites and stalagmites are the two most basic and well-known formations, captivating visitors with their intricate and natural beauty.

Read on to discover the key differences between stalactites and stalagmites, how they form, and the fascinating facts behind these underground wonders.

What are stalactites and stalagmites?

The word stalactite originates from the Greek word stalaktós, meaning “dripping” or “that which drips,” while stalagmite comes from stalagmías, meaning “the result of dripping.” These self-explanatory names reflect their formation processes. Both stalactites and stalagmites are driven by the slow yet continuous deposition of minerals, typically composed of calcium carbonate (CaCO3), from dripping water.

Stalactites form on the ceilings of limestone caves when mineral-rich water seeps through rock and leaves behind deposits, primarily calcium carbonate. Over time, these deposits accumulate, growing downward in a tapering, icicle-like shape. In contrast, stalagmites grow upward from the cave floor, forming when water droplets carrying dissolved minerals land on the ground, leaving behind layers of sediment.

But why does dripping water in limestone caves even contain minerals like calcium carbonate? This is because this water originates from rainwater that seeps through soil and absorbs carbon dioxide (CO2) from organic materials, forming a weak carbonic acid solution. As this slightly acidic water seeps through limestone rock, it dissolves calcium carbonate from the surrounding stone, carrying it into the cave.

How do stalactites and stalagmites form?

As explained, stalactites and stalagmites form through the deposition of calcium carbonate and other minerals, which precipitate from mineralized water solutions dripping inside caves. However, not all stalactites and stalagmites are speleothems.

While speleothems are specifically formed in natural limestone caves, similar structures can occur in other environments, such as mines, tunnels, and even concrete structures. These structures are known as secondary deposits rather than true speleothems.

The average growth rate of stalactites and stalagmites is extremely slow, typically around 0.1 mm per year or 10 cm every one thousand years. Even the quickest-growing stalactites and stalagmites ever recorded can only grow 3 mm per year.

This rate is influenced by several factors, including:

- The concentration of dissolved minerals in the water;

- The cave’s temperature and humidity;

- The speed at which water drips from the ceiling.

The drip rate plays a crucial role in determining whether a stalactite or a stalagmite forms. If the drip rate is slow enough, carbon dioxide in the water degasses into the cave atmosphere before the droplet falls, causing calcium carbonate to be deposited on the stalactite. If the drip rate is too fast, the solution retains much of its dissolved minerals until it reaches the floor, leading to the formation of a stalagmite.

Stalactite and stalagmite formation generally begins over a large surface area, but as mineral-rich water flows through multiple microscopic channels, one channel tends to dissolve more minerals, eventually drawing more water and dominating the others. This natural competition results in distinct formations with a minimum distance between them, with larger formations requiring more space to grow.

Differences between stalactites and stalagmites

Stalactites and stalagmites may appear similar, but they have distinct differences in formation, location, shape, and growth processes within caves.

| Feature | Stalactites | Stalagmites |

| Location | Hang from the ceiling of caves | Rise from the floor of caves |

| Formation process | Form as mineral-rich water drips and deposits calcium carbonate before falling | Form when mineral-rich water drips onto the cave floor and deposits calcium carbonate |

| Shape | Typically icicle-shaped, tapering downward | Often mound-like or cone-shaped, growing upward |

| Drip rate effect | Requires a slow drip rate for CO2 degassing to occur before the drop falls | Forms when the drip rate is faster, allowing mineral deposition on the ground |

| Connectivity | Can eventually connect with a stalagmite to form a column | Can merge with a stalactite to create a column |

| Etymology | From the Greek stalaktós (dripping) | From the Greek stalagmías (the result of dripping) |

| Growth rate | Typically very slow, averaging 0.1 mm per year | Similar slow growth rate, dependent on conditions |

Types of stalactites and stalagmites

Stalactites and stalagmites come in various types, forming through different processes in limestone caves, lava tubes, and icy environments.

Limestone stalactites and stalagmites

Limestone stalactites and stalagmites develop in limestone caves through the slow deposition of calcium carbonate from mineral-rich dripping water. These formations are commonly found in limestone caves worldwide, including:

- Phong Nha – Ke Bang National Park, Quang Binh, Vietnam;

- Mammoth Cave National Park, Kentucky, US;

- Carlsbad Caverns National Park, New Mexico, US;

- Cumberland Caverns, Tennessee, US;

- Oregon Caves National Monument and Preserve, Oregon, US;

- Wind Cave National Park, South Dakota, US;

- Russell Cave National Monument, Alabama, US;

- Jewel Cave National Monument, South Dakota, US;

- King Otto, Bavaria, Germany;

- Jenolan Caves, New South Wales, Australia.

Lava stalactites and stalagmites

Unlike limestone formations, lava stalactites and stalagmites form rapidly in lava tubes as molten rock drips from the ceiling and cools. This process occurs within weeks, days, or even hours as the lava solidifies. Stalactites form as lava drips and harden midair, while stalagmites develop when lava droplets accumulate and cool on the floor. Due to the viscosity of lava, stalactites are often jagged, while stalagmites are often stubby.

A major distinction between lava and limestone stalactites and stalagmites is that once lava stops flowing, the formations halt their growth as well. As a result, if a lava stalactite or stalagmite is broken, it will never regenerate. Lava stalactites and stalagmites are commonly found in volcanic regions, particularly in lava tubes such as Hawaii’s Thurston Lava Tube or Hana Lava Tube and Iceland’s extensive lava caves.

Ice stalactites and stalagmites

Ice stalactites and stalagmites form through the freezing of dripping water in cold environments. When water drips from an overhanging surface in freezing temperatures, it solidifies into an icicle-like ice stalactite. If the dripping water accumulates and freezes on the ground, it creates an upward-growing ice stalagmite. Ice stalactites are elongated and taper downward, whereas ice stalagmites take conical or irregular forms.

Ice stalactites and stalagmites aren’t considered speleothems. Like lava stalactites, ice stalactites can develop rapidly within hours or days. However, they can regrow if water continues to drip and temperatures remain cold enough. These formations occur in ice caves, glaciers, and other frigid environments, including the Eisriesenwelt Ice Cave in Austria and natural ice formations in the Arctic and Antarctic regions.

Forms of stalactites and stalagmites

So far, a total of 38 different types of true speleothems (limestone) have been identified across the world. Here are the most common forms:

Column (pillar)

A column, or pillar, forms when a stalactite and a stalagmite in the same vertical axis grow long enough to merge into a single continuous structure. These formations vary in shape and size, ranging from slender and smooth to rounded, massive, and irregular, depending on water flow and mineral deposition. Columns can create dramatic cave interiors, sometimes resembling towering stone pillars or tree trunks.

Drapery

Drapery formations develop when mineral-rich water flows down a sloped ceiling, depositing thin, sheet-like layers of calcite. These formations resemble delicate curtains or folded fabric, often featuring intricate patterns and translucent bands. The wavy, flowing appearance results from variations in water flow and mineral content, making drapery one of the most visually striking speleothems in limestone caves.

Dripstone (flowstone)

Flowstones, also known as dripstones, are sheet-like deposits that form when mineral-rich water spreads over cave walls or floors, creating layers of calcite or other minerals. These formations often appear as smooth, rippling sheets that resemble frozen waterfalls or cascading rock. Flowstone can cover large cave surfaces, with shapes influenced by water flow speed, mineral content, and underlying rock formations.

Soda straw

Soda straws are thin, hollow stalactites that form as water drips from a single point, leaving behind a ring of calcite. These delicate formations grow downward in long, slender tubes, often only a few millimeters wide. Because they remain hollow, soda straws are fragile and easily broken, but under the right conditions, they can transition into solid stalactites. Nearly all stalactites start their life as soda straws.

Interesting facts about stalactites and stalagmites

Records

Here are some notable records related to stalactites and stalagmites:

Longest stalactite

The longest stalactite in the world, measuring 28 m (92 ft), is located in Gruta do Janelao in Minas Gerais, Brazil.

Tallest stalagmite

The tallest known stalagmite in the world stands 80 m (260 ft) high and is located in Son Doong Cave in Phong Nha – Ke Bang, Vietnam.

Largest cave column

The tallest known cave column stands at 61.5 m (201 ft 8) and is located in a cave in Tham Sao Hin, Thailand.

Fastest growing stalactites and stalagmites

The quickest growth rate recorded is 3 mm per year, observed in caves with highly mineralized water and optimal conditions.

Etymology

Interestingly, the etymology of speleothems reflects their resemblance to familiar natural or man-made objects. For example, soda straws are thin, hollow stalactites resembling drinking straws, while chandeliers are clusters of stalactites resembling ornate light fixtures. Ribbons and broomsticks describe long, thin formations, while drapery, also known as cave bacon, refers to thin, wavy sheets resembling fabric or strips of bacon.

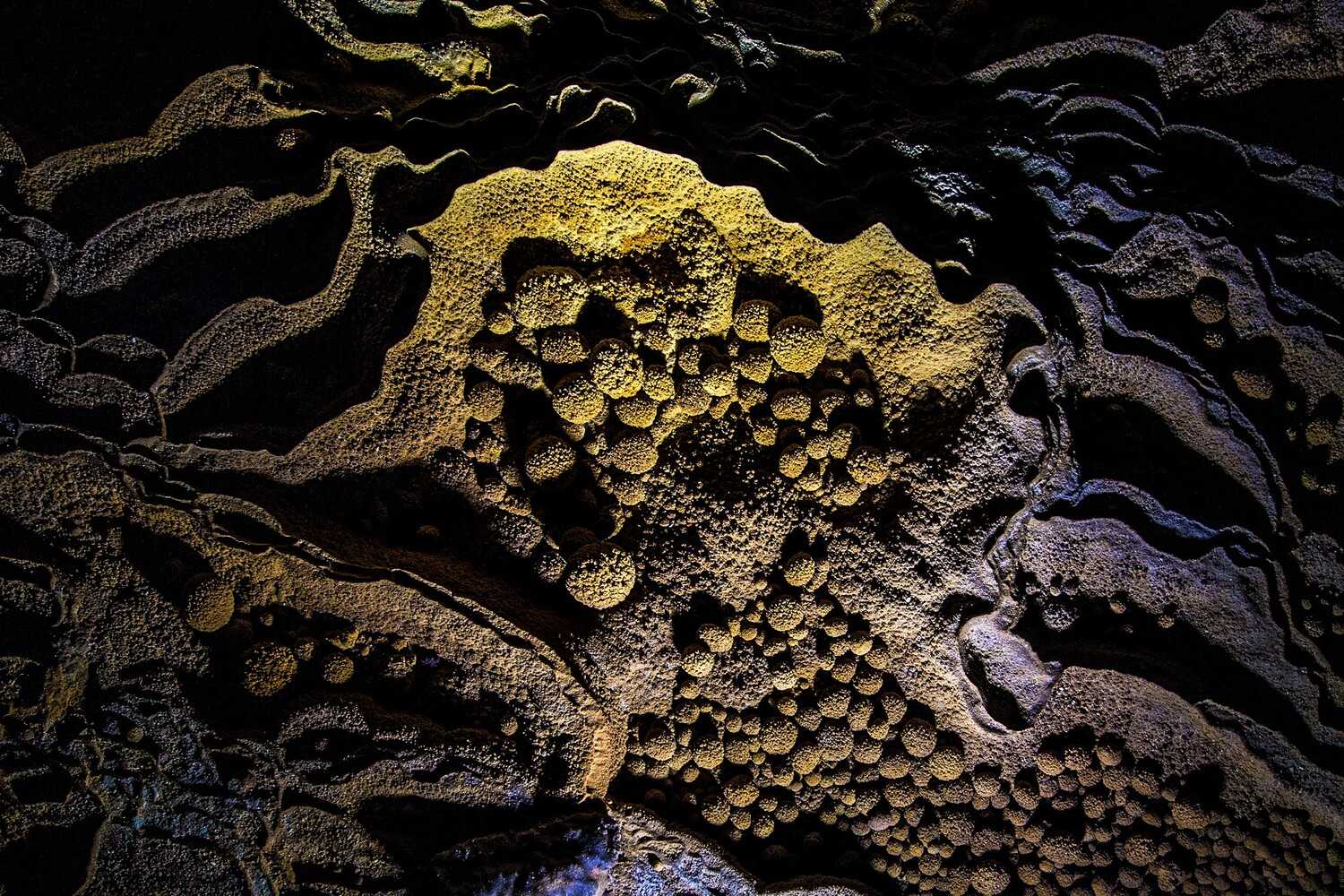

Meanwhile, popcorn formations appear as knobby clusters, while cave pearls are among the most fascinating speleothems. These pearls form when water drips from high above, continuously turning small seed crystals. This allows layers of calcium carbonate to build up into smooth, nearly perfect spheres over time. Constant water movement buffs cave pearls to a shiny finish, but if left out to dry, they can lose their shine and turn rough.

Preservation

Preserving stalactites and stalagmites is crucial for maintaining their natural growth and beauty. The rule is simple: no touching. Skin oils disrupt the process of mineral deposition, potentially altering their growth. Even a small touch can affect how water clings to the surface, slowing or stopping formation. Also, dirt, mud, or clay from human contact can stain and discolor these fragile structures, damaging them forever.

Which of these cave wonders fascinates you the most—stalactites hanging like nature’s chandeliers or stalagmites rising from the ground? Either way, both create breathtaking underground landscapes worth exploring and preserving!

Source: Internet